By Douglas Phillips

This article is about all the women who contributed to the Canadian World War Two war effort on the Home Front, especially those who worked in the munition plants. Like our veterans there are just a few left and on this Remembrance Day we need to salute them and thank them for their service to this country. It is also a story about a town on the shores of Lake Ontario. In the summer of 1939 if you travelled east along Highway 2 from Toronto, you would go through Scarborough, Pickering and Whitby. These were all small villages surrounded by rolling farmland. Today it is hard to imagine what it must have looked like then, as now they are all urban communities, rapidly growing with town halls, shopping centres and schools. After you pass Pickering today, you come to the town of Ajax, but in the summer of 1939 Ajax did not exist. It is a town literally born out of the Second World War. What was accomplished at Ajax made a tremendous impact to the war effort, and this was due mostly to the women of Canada.

Canada was not prepared for war. Before 1939 the country was divided and wracked by economic depression, and Canada’s 11 million people were struggling to survive after the Great Depression. Canada was poor and the gross national product was only $5.6 billion. There was a huge need for a steady supply of bullets and bombs. Our Allies looked to Canada for equipment and munitions. In addition, Canada was far enough away from the conflict to be able to supply the necessary armaments without threat of attack. Canada’s situation would drastically change over the next five years and the nation that emerged after World War Two would become rich and powerful, confident and secure. The war changed everything for Canadians at home and women would play a key role in helping with war production – 48,000 women enlisted in the armed services. Canada was a member of the British Empire, and on September 9 British Parliament sent a message to London. On September 10, 1939 King George VI declared that Canada was at war. At the start of the war the country’s military forces were very small, with old equipment, no tanks, no modern artillery, no anti-aircraft guns, and hardly any trucks. The navy had few ships and little ammunition. The air force only had ancient vintage aircraft.

How did the country pull together and meet the challenge? The government needed a plan and appointed American-born Clarence Decatur Howe. He was trained as an engineer at MIT, Mass, USA and then came north to teach at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. PM Mackenzie King made him Canada’s wartime industrial czar. Howe was tough, smart, and he chose the captains of industries called “dollar-a-year” men who paid their own expenses. There were challenges every day – shortage of supplies, raw materials, and workers, but he always got what he needed.

The government created twenty-eight Crown corporations to boost war production across the country, and new plants were built or old ones updated. In Oshawa and Windsor car plants produced trucks, armoured vehicles tanks and Bren gun carriers. Fort William (Thunder Bay) built Hurricane fighter planes, Victory Aircraft in Malton produced Lancaster bombers. Winnipeg built Anson aircraft for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Ships were needed, and corvettes for convoy duty across the Atlantic were built in Collingwood, and cargo ships from the shipyards in Quebec. The Canadian Forces and Allied Armies needed munitions, millions of shells, bullets and bombs to win the battles in Normandy and Italy. All that was needed to win the war Canada produced, from radio sets to canned food to feed Britain; overnight Canada became an industrial war machine.

Women took over the jobs that men had always done, driving buses and streetcars, civil service jobs and service in industry. At its wartime peak in 1943-44 there were 439,000 women employed in the service sector, and 373,000 in munitions factories, making everything from Bren guns to aircraft to corvettes. A woman’s lighter touch meant faster work on operations needing dexterity, they were better at inspection because they paid more attention to detail and had much more patience. Women also showed great skill in production planning, routing and control of operations connected with production, drafting, tool crib and store tending, dispatching and timekeeping. In the UK and Canada, per the Inspection Board, there were more than 8,000 unskilled and 350 skilled inspectors; all women. Their work included passing on munitions, inspecting gun barrels and gun carriage parts, explosives, radio equipment and rejected materials.

Defence Industries Limited (DIL)

In February of 1940 two army surveyors arrived in Pickering to view the proposed site for a shell filling plant. The land they proposed met all conditions. It was close to a railway line for shipping needs, it was by Lake Ontario for fresh water, and Whitby was nearby for electrical power. Approximately 3,000 acres of farmland was expropriated for the plant. By Christmas of 1941 the Defense Industries Limited (DIL) plant in Pickering was complete. DIL would grow to 9,000 employees and become the largest munitions production factory in the British Empire.

A very large amount of labour was needed. People came from nearby locations to the factory, often by special bus transportation, but the government soon realized to meet the production quotas more people were required. A nation-wide advertising recruitment campaign began, and women answered the call through the National Selective Service. They mainly came from the Prairies and the Maritimes travelling for days on trains. For many this was the first time they had left their hometown, but after the Depression the promise of a good job and decent money was a big incentive. Women also felt it was their patriotic duty to serve on the Home Front. Train fare was provided but if after three months, the employee wished to return home, train fare was also provided for the return trip. To help with recruitment, the government commenced a propaganda machine that portrayed posters of attractive, smiling young women, hair covered in bandanas and draped in coveralls producing the munitions Canada needed for the war effort.

With so many women arriving from outside the local area to work on the DIL lines, there was a great need for housing. The construction of government homes near the plant began in January of 1942. DIL constructed a total of 21 residences, to each housing 100 persons. A room was shared by two girls. They were comfortable but not luxurious. A very large cafeteria supplied a variety of food and drink for meals, and on weekends. A beauty shop was also provided. For administrative staff and visitors, willing to pay for amenities not available in the residences, the company provided a sizable hotel, named Arbor Lodge. This could accommodate 250 people. DIL also built five houses for top officials, the plant manager, his assistant and officers working under the plant manager. Five more houses and three small apartment blocks were built for line supervisors. (Many of these houses are in good condition and are still occupied by long-time residents of Ajax.)

Most of the workers were of Anglo-Canadian backgrounds. Everyone employee was fingerprinted and photographed, and backgrounds checked by the RCMP. They had to have a DIL pass with a number and a picture, always to be readily visible. The whole plant was surrounded by a security fence with barb wire. The fence was lit during the night, with constant fence patrols, and the guards were armed with shotguns and ammunition. The guards checked all passes, in and out, and questioned persons if they were in possession of matches or other flame-producing articles. Random searches of employees were also carried out, going in and leaving the plant. Guards were everywhere. Despite having a valid pass, employees could only be on the premises during their scheduled shifts. No smoking anywhere near the premises for fear of fire. Of all the factories across the country, the munitions factories were the most dangerous. There were three shifts per day, for six days a week. All employees went through stern orientation lectures, reinforcing plant safety protocol. They were given a handbook which stated employees must appreciate that the manufacture of ammunition had inherent hazards. Safety was top priority.

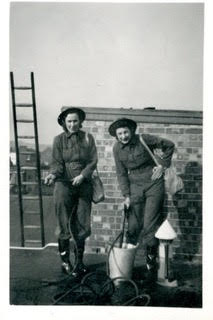

At the start of their shift, the worker passed through the Gate to go to what was called the “clean area.” This was imperative. A single spark could be catastrophic, and to guard against this possibility workers were provided with a clean area called a change house. Women had to strip down to cotton bra, panties and socks. They had to be free of anything that might cause static electricity or ignite a spark. No metal on bras, no flammable materials such as artificial silk and flannelette, no hairpins. Nail polish and any kind of jewelry was not allowed. Hair had to be completely covered under a bandana, and metal clasps on bras were replaced with buttons. DIL provided bandanas to cover the hair, and these were colour coded for specific shifts/lines. Men wore white cotton caps.

After removing their street shoes, they carried their clean area shoes to the barrier, where they stepped over it into the clean area, thus avoiding carrying any grit into the production line. The clean area shoes were specially made without any metal whatsoever. Every Line had a clean house. At the end of the shift, employees went from the clean area over a low barrier to pick up their street clothes until their next shift. Each employee was given a locker and a coverall, or smock. Coveralls were mandatory.

There were four Lines at DIL, with the bulk of the work done by women. Most of the dangerous work was around the amatol and TNT, and the assembly of shell filling. The constant fear of producing a single fatal spark, or causing an accident through a miscalculation or lack of care must have been very stressful. Their hands and fingers were protected by leather gloves up to the wrists. Fingers and thumbs were exposed for the delicate task of loading caps. Working with explosive charges was extremely dangerous, because the slightest force, a static spark or any friction could cause the powder to explode. Static electricity was an ever-present risk, and to eliminate the possibility of sparks, every building and every piece of machinery was individually grounded with a heavy copper strap running continuously through every part of the building. Despite all the risks the women carried on shift after shift, and year after year until the war was over.

Winding down of DIL

As the Allies closed in on Germany and the Third Reich crumbled, shell production began to wind down in 1944. Stockpiles were reduced and several lines were shut down. With Victory in Europe on the 8 May 1945 the lines stopped working and by July the plant was closed except for cleanup and dismantling crews. The residences were abandoned and the “Bomb Girls” were issued pink slips. The Government Unemployed Insurance Program provided some support and the cashing in of Victory Bonds helped. Some workers returned home while others decided to stay in Ajax, live and raise families in the war time housing. The plant buildings were systematically demolished except for a few residential buildings.

A Lasting Tribute to the Bomb Girls

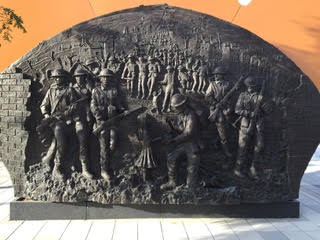

The women at DIL reflected Canada’s war effort, large amounts of ammunition were produced in the four years. They worked tirelessly with only five deaths from industrial accidents. The work was arduous and dangerous and workers were sonstantly exposed to chemicals and explosives. Despite the dangers, absenteeism and the staff turnover was low. They donated $3millon to Victory Loans, supported the Red Cross appeals, gave aid to Russia and donated blood. Their courage, determination and contribution helped win the war so we all could live in freedom. A special memorial paying homage to the DIL women munition workers has been crafted by local artist Walter Schultz. This memorial represents actual workers and soldiers in a two-sided monument, utilizing photographs of each group. The monument can be seen at the Pat Bayly Civic Square in downtown Ajax, showing the critical role DIL Ajax played on the Canadian Home Front supplying 40 million units of munitions for the war effort.

The Naming of Ajax

Before the war there was not a town named Ajax. By midsummer of 1941 almost 3,00 workers were living at DIL. The nearby town of Pickering’s post office could not cope with the overload of official communications, therefore DIL decided to provide their own post office, but what to name it? DIL decided to hold a competition, with a small prize for the winner. The winner was Frank Holroyd, assistant safety director. He proposed “Ajax.” The British warship H.M.S. Ajax had just distinguished herself in a protracted battle with the German pocket battleship Graf Spee. The Ajax followed the much larger German ship for four days and nights, keeping her under constant attack. Assisting her were H.M.S. Achilles and H.M.S. Exeter. The Exeter was disabled, and the Achilles, though badly damaged, continued to fight. Despite suffering heavy damage from the Graf Spee’s 11” guns, the Ajax continued to lead the attack. The German ship, severely damaged, took shelter in the neutral harbour of the River Plate at Montevideo, Uruguay. Under international law, the Graf Spee could only stay there a limited amount of time. When this time had elapsed, the ship left the harbour, and Admiral Langsdorf, rather than allow the ship to be taken by the British, scuttled the ship outside the harbour. The battle had started on December 13 and ended on December 17, 1939. Because of the courage and resolute action in her log, the H.M.S. Ajax was readily accepted as the symbol to represent the new plant and the new post office was officially named Ajax. Today the main street in Ajax is named after Rear Admiral Harwood who commanded the British Squadron. Many other streets are also named after the ship’s crew. The Ajax’s anchor is on display at the local Royal Canadian Legion.

This story is dedicated to all the women who contributed to the war effort and my Mother who worked as a Bomb Girl in England.

- Footnotes Ajax The War Years 1939/45- Ken Smith 1989

- Back the Attack; Canadian Women During the Second World War- Jean Bruce 1985

- The Last Good War 1939-1945 – Dr. J.L. Granatstein 2005

- Sincere thanks to Records Branch, Town of Ajax, for their assitance with this article.